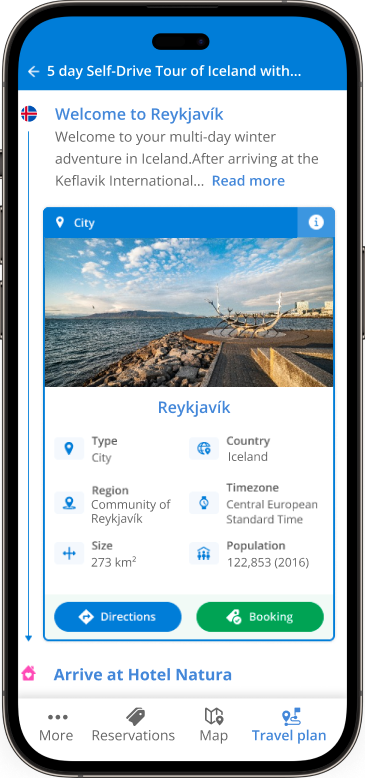

This is the time of year when we Icelanders experience the so-called jólabókaflóð, or “Christmas book flood”. Iceland publishes more books per capita than any other country in the world and the bulk of book sales happens at this time of year, with the publishing industry receiving something like 80 percent of its annual revenues in the approximately two months leading up to Christmas.

The main reason for this deluge is the longstanding tradition in Iceland of giving books as Christmas presents - each and every Icelander typically receives at least one book under the tree each year. After opening the presents on Christmas Eve, many people revel in the thought of crawling in between the covers with something new to read.

As you might surmise, books are a highly topical subject in Iceland during the book flood. The annual Bókatíðindi book catalogue, containing around 700 titles, arrived in our mailboxes last week, and people have started asking each other what they think of the new books coming out, what they’re looking forward to reading, etcetera. Loads of space and airtime in the media is given over to book reviews, discussions, interviews, deliberations about the best and worst book covers … basically any possible angle to do with books. After Christmas, the same topic is popular around the watercooler, with people talking about what they thought of the books they read, whether it was better or worse than that author’s last book, and so on.

So … why this Big Love for books in Iceland? Why have the Icelanders, in particular, cultivated such a love and appreciation of the written word?

- See Also: Icelandic Literature for Beginners

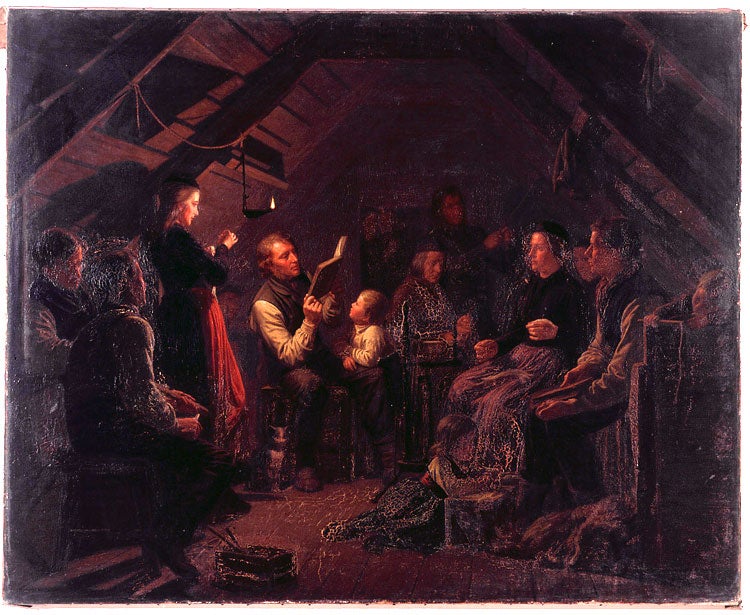

What really helped the Icelanders survive those times of adversity was the memory of the era when the Sagas were written, when they were still proud and independent. It gave them a sense of national identity and pride. At this time the country was intensely poor, all firewood had been stripped from the land, and people were forced to live in small turf houses, all huddled together for warmth. Because the winters were long, dark and harsh, folks had to spend many hours indoors, and a tradition developed in the evenings for something called a kvöldvaka. This was basically a storytelling session in the communal living area, to keep people awake and entertained while they did their “winter work” – spinning wool, knitting, making tools and so on. Someone would read from a book, people would tell stories, or recite poetry. Sometimes verses would be made up on the spot, with someone making up one line, someone else having to contribute the next line, and so on. During those long winter evenings, the kvöldvaka was an essential part of keeping people spiritually alive.

The kvöldvaka was also where the education of children took place. They were taught to read and write, and learned about history and geography through the telling and re-telling of the Sagas and other stories. It is considered very unique, for example, that even though the nation was so alarmingly poor, almost everyone could read and write.

In addition to this, the Icelanders seem to have had a strange compulsion to record the events around them. The National and University Library has a section in which centuries-old journals and diaries are kept. Anyone can read those journals, in which regular Icelanders recorded aspects of their day-to-day lives, and which contain lines like this one, taken from an actual diary: “There is frost outside, yet it is calm. My daughter died last night.”

And so, books to us Icelanders are far more than mere entertainment. They are an intrinsic part of our national identity, and remind us of the resilience of our ancestors and how far we have come since then.

For more on the Icelanders, present and past, you may want to check out Alda’s The Little Book of the Icelanders, and The Little Book of the Icelanders in the Old Days.