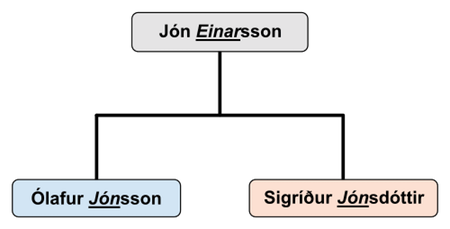

Icelandic naming tradition uses a patronymic or, more rarely, matronymic system, meaning the suffix -son ('son') or -dóttir ('daughter') is added to the genitive form of the father's name, ie. Ólafur Jónsson is the son of Jón Einarsson.

Names in Iceland must also be pre-approved by law—but who holds the authority to accept what names are and are not acceptable? Read on to find out more about the mysterious minds of the Icelandic Naming Committee.

Names are funny, aren’t they?

If your answer is ‘not particularly’, I would resoundingly agree with you, save for two obvious exceptions; celebrity-babies and Icelanders.

- See also: Icelandic Literature for Beginners.

I say celebrity-babies because the creativity of artists tends to get a little hairy when it comes to naming their young; more often than not, these tykes end up being named after multi-million dollar corporations, fruit, toilet products or directions; Apple, Blue Ivy, North, Audio, Cosimo, Coco… the list goes on.

Header Photo. Wikimedia. Creative Commons. Eviatar Bach.

I bring Icelanders into the mix because, in many respects, they are the cultural antithesis of naming your children strangely. In fact, this small island of just over 300,000 people is regulated by a number of laws that stipulate exactly which name you can and cannot deem acceptable for society.

Authorisation lies at the feet of the Icelandic Naming Committee, aka; Personal Names Committee (“Mannanafnanefnd”).

Sure, this has slight Orwellian undertones, but there is wiggle-room for parents unimpressed by the restrictions. Whilst applications can be made to introduce names onto the approved list, the naming committee has, in the past, had big problems with introducing the likes of “Harriet” and “Pedro” into the lexicon.

And yet, you are more than allowed to name your child: Bergljót, Dögg, Hálfdan, Valdimar, Jens. Grímur, Gróa, Eirný, Dagfinnur, Greipur. In fact, there are over 1700 male names and 1800 female names to choose from.

The name “Duncan”... and the letter “c” are strict taboos, however.

Whilst researching the traditions of Icelandic naming, I stumbled across a list of names rejected by the Icelandic Naming Committee, including those for boys, girls and families.

Among the rejected first names were Woman, Spartacus, Princess, Viking, Eagle and Layla. There were normal rejections too such as Toby, Jerry, Zoe and Jennifer, which makes one ponder quite what the naming committee is looking for.

- See also: 10 Reasons Icelanders are Proud of Iceland.

I was pleasantly surprised to find someone applied to be known as “X the Icelandic”. Another person identifies with the name “Stone Fireplaces”, and another considers his rightful name to be “Arrows”.

By the default of birth, we have no choice over what we’re called (for reasons known only to themselves, my parents were on the dangerous cusp of naming me Amadeus, for Christ's sake), yet, over time, our names come to have meaning and value. It is a matter of reputation, be it the realms of employment, friends or family.

Take one of the best-known cases in Iceland that showcased a direct disaccord between then-Mayor and comedian, Jón Gnarr, and the Icelandic Naming Committee. His request to legally drop the name ‘Kristinsson’ was denied by the board, despite his argument that he wished to disassociate himself with his father.

- See also: International Relations of Iceland.

The comedian ruefully pointed out that should Zimbabwe’s dictator, Robert Mugabe, decide to emigrate to Iceland, he would be entitled to keep the non-conforming “Mugabe”, despite its irreverence for Icelandic culture. He, on the other hand, a native Icelander and working politician, would not be able to do so.

On point, Jón labelled the committee “discriminatory,” claiming the laws only applied to a minority of Icelandic people. On his Facebook page, he posted a status reading;

“In Iceland, you can be named Jesus. The Name Committee can’t stop that. It doesn’t matter if you spell it with a 'ú' or a 'u'. You can also be named Muhamed or Muhammed. The naming laws pertain mostly to only a fraction of Icelanders. What kind of law discriminates against people in this way?

Why, for example, may Elín Hirst have the surname Hirst but I can’t have Gnarr? Is Hirst cooler? More Icelandic? Are all animals equal, but some are more equal than others? In Jesus’ name, answer me!”

- See also: History & Culture in Iceland.

At the same time, Jón wished to legally name his daughter “Camilla”, after his grandmother. Once again, the Icelandic Naming Committee decided that this was inappropriate given the fact that there is no “c” in the Icelandic language. At the end of the dispute, Jón chose to name his name his daughter “Kamilla” (‘K’ is in the Icelandic alphabet), and was legally allowed to drop his name in 2015.

But on what grounds does the Icelandic Naming Committee have to determine what is and what’s not acceptable? Well, for one thing, their parent committee is the Ministry of Justice, part of the official Icelandic government, and has been operating since 1991.

It was decided that new given names must be considered in relation to their historicity—that is, how well they will integrate into Icelandic culture, and whether they previously have been used before.

- See also: The Most Infamous Icelanders in History.

Another stipulation under Article 5 of the Personal Names Act dictates that names must be compatible with Icelandic grammar rules and only contain letters officially in the Icelandic alphabet. The committee also weighs up whether the new name will cause embarrassment to those who bear it.

So, with that reeling in our minds, let’s take a closer look at some other cases involving names thought worthy of contention by the committee. One such example would be that of native Icelander, Blær Bjarkardóttir Rúnarsdóttir (born 1997) who wished to be registered under her given name, ‘Blær’.

The committee denied this request, claiming the masculine noun Blær, meaning “gentle breeze”, could only ever be used as a man’s name.

Upon appeal. Blær and her mother, Björk Eiðsdóttir, argued that Nobel Prize-winning author, Halldor Laxness, named a female character Blær in the 1957 novel “The Fish Can Sing”.

They also pointed out that another woman named Blær was living in Iceland at that time, and in fact, that Blær has two case forms, a masculine and a feminine, meaning it could be used either way. Throughout the proceedings, Blær’s legal registrar was “Stúlka”, meaning “girl” in Icelandic.

- See also: History of Iceland.

The Reykjavík District Court ruled in favour of the family at the beginning of 2013, prompting the committee to ponder whether the Icelandic government would revisit their current legislation relating to Icelandic names.

The latest case follows the story of Duncan and Harriet Cardew—or should I say Drengur (boy) and Stúlka Cardew—two Icelandic born kids of a British father and Icelandic mother. In 2014, the Icelandic authorities refused to renew their passports unless the pair changed their names to something legally acceptable.

This, unfortunately, couldn’t have a come at worse time for the Cardew family as they were only days away from a holiday to France. The Cardews promptly lodged a complaint and case against both the Icelandic Naming Committee and the passport office, finally winning their case in 2016.

As of today, both Duncan and Harriet are acceptable, though it has been a struggle to get there. As a result of the case, the Interior Ministry of Iceland announced that it was beginning the process of abolishing the Naming Committee completely, despite the fact this legislation has yet to go through the parliamentary process.

So it would seem the Icelandic Naming Committee is on its last legs; whilst noble in ambition, it would seem the Icelanders are conflicted when it comes down to choosing between the preservation of culture and the societal freedom to choose exactly what they call their children.

Until the committee is abolished, we can only ponder what changes might come into effect… my lingering hope, at any rate, is that Iceland might come to get more "Duncans", and feel less pressure to outlandishly nickname themselves “Arrows”.