Iceland has long been known for tall tales of tall heroes and their incredible strength. Some of Iceland's best-known cultural icons, in fact, are the country's log-lifting and rock hauling strongmen.

But where does Iceland's love of strength come from? And how does a nation consisting of just over 300,000 people produce an outstanding number of 'world's-strongest' men and women?

Photo above from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Jose Lu. No edits made.

- Find out more information in Fitness in Iceland | Sports, Exercise and Wellbeing

- Check out this brilliant Westfjords Cycling Tour | Raudasandur Beach

- Why not partake in this Birds, Beaches & Beauty | Westfjords Cycling Tour

- See also Top 9 Most Famous Icelanders in History

The Strength of a Nation

Iceland boasts of some of the strongest people in the world. With names like Jón Páll Sigmarsson, Magnús Ver Magnússon and Hafþór Júlíus Björnsson—the Mountain from Game of Thrones—Iceland has cemented itself as a veritable breeding ground for giants.

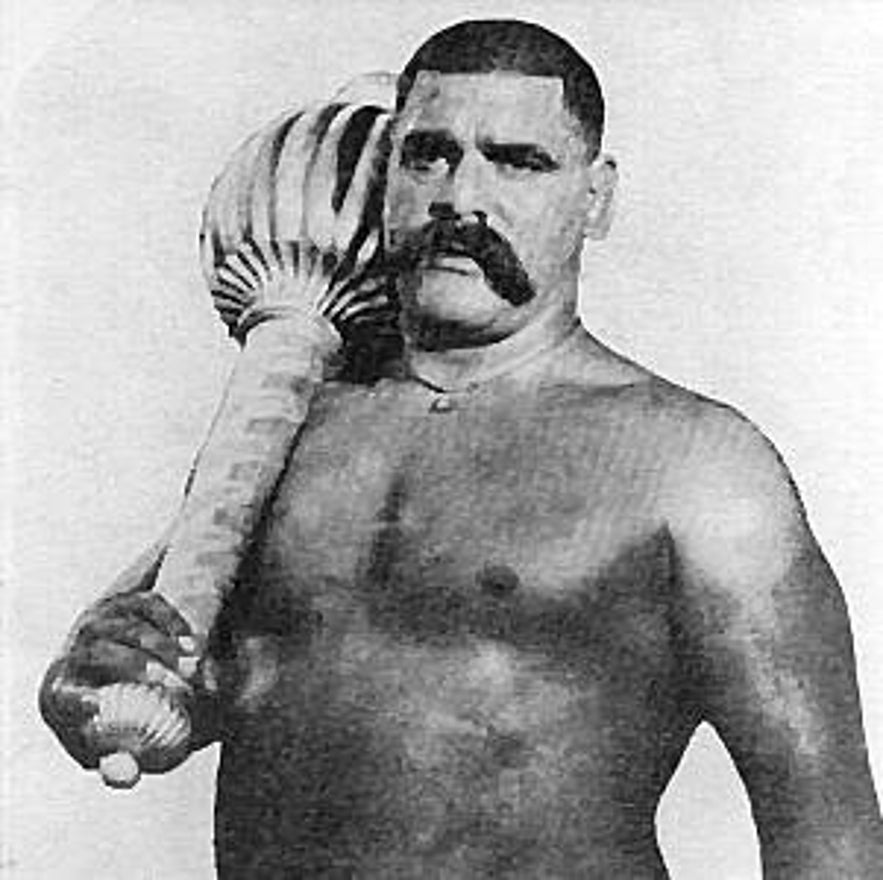

Originally, the word 'strongman' was used to describe militant leaders who’d keep command by their sheer force of will, rather than raw physical strength or other less savoury methods. It was only later, during the mid 19th century, that the word became linked to circus acts, striped bodysuits, handlebar moustaches and specific forms of strength athletics.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Pahari Sahib. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Pahari Sahib. No edits made.

The modern-day strongman, however, is a phenomenon we’re more accustomed to seeing in films and advertising than on the battlefield. The word has come to symbolise a man who competes in what Icelanders call Aflraunir ('tests of strength') as opposed to Kraftlyftingar (power- and weight lifting).

Throughout history, physical strength has always been fundamental to survival in Iceland, a land of rough and unforgiving natural conditions that require everyone to pull their own weight.

Well into the 20th century, the women of Iceland's capital, Reykjavík, hoisted washing loads from the city centre over a distance of five kilometres to the pools in Laugardalur—before having to carry all their equipment back home, along with the mountains of wet laundry, after 10 hours of washing.

Because of the share weight of these loads, foreign travellers considered this daily routine such a super human feat, that they often likened the strength of the Icelandic 'washing woman' to the power of a pack horse.

- See also: Gender Equality in Iceland

Meanwhile, Icelandic men carried builders and large rocks from the fields to make turf houses and drew enormous fishing nets from the sea by hand; strong sailors were in great demand and a man's true worth was easily determined by having him lift enormous stones.

Throughout recorded history, Icelanders tested their strength on specific rocks, the most famous being the Húsafell stone, weighing 186kg (409lbs). A Fullsterkur status (a person of 'Full Strength') was only gained by hoisting, carrying and placing a rock of 155kg or heavier on a platform waist height or higher.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Chris 73. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Chris 73. No edits made.

Iceland has a strong and long running power sports tradition. Competing in Icelandic wrestling, Glíma, was traditionally done by both genders, where the primary objective was to throw your opponents over your head and to the ground.

Marathons have never been particularly popular in Iceland (probably because of the weather) but the warrior prowess has always been an easy sell, possibly because of our history, and the romanticisation of the giants and warriors of ancient legends. Before football, Icelanders had pure strength.

A large selection of fitness options in Iceland focuses on strength, protein intake and a clean diet. Icelandic women practice weight lifting as a normal part of any workout routine, and competitions where teens between 14 and 16 compete by running through Crossfit style obstacle courses, are nationally televised and subject to great attention.

You’re never too young for fitness. After all, Icelanders are the nation that invented Lazytown.

Even though the Icelandic Strongman is clearly the most famous of Iceland's power icons and was the hailed hero in the 1990’s, the country is home to plenty of women who are not afraid to rip iron.

Two Icelandic superwomen, Katrín Tanja and Anníe Mist, hold two titles each as World champions in Crossfit; weightlifter Ragnheiður Sara Sigmundardóttir is known across the world for her strength and physical prowess; and the up and coming Sóley Jónsdóttir, recently won the European powerlifting championships in her age and weight category, by performing an astonishing 215kg squat—at the tender age of 15.

The Giants of Iceland

I don’t know what those Icelanders are eating, but I need to go over there and try some of that. – O.D. Wilson

The glorification of raw strength is nothing new in Iceland. Perhaps the most obvious icons historically are the Old Norse Gods, most specifically Þór, God of Thunder, Wrestling and Fertility, and Týr, God of War and Tactics. Both were described as fiercely fit and strong, though Týr used his brain a lot, while Þór tended to smash things with his hammer.

As strange as it sounds, one of Þór's greatest achievement was lifting a cat. The cat in question, however, was a feline embodiment of the great Miðgarðsormur wyrm, a terrible beast which encircles the earth and cannot be lifted as it is all-encompassing. Þór, however, was strong enough to hoist it so high that the cat had to lift its hind leg. He could not achieve the impossible and pick it up, but he came close.

- Read more about Folklore of Iceland here

When the Old Gods were weaned out of Icelandic culture during the transition to Christianity and later through the Reformation, strength was still idealised through myths of trolls and giants and, of course, the Vikings and Chieftains of the Icelandic Sagas.

These Sagas are filled with strong people, both mentally and physically, though specific heroes are seen as notable representatives of human strength. Gunnar Hámundarson and Skarphéðinn Njálsson, both from Brennu-Njáls Saga, were described as big and strong, with Gunnar being able to run a man through with a spear before using the impaled body as a bludgeoning weapon on the remaining foes.

Tall tales of tall men, certainly, but the uncrowned King of Strength and lauded still as the strongest man ever to walk on Icelandic soil, is Grettir ‘The Strong’ Ásmundarson. His physical power dwarfed the heroes of old and earned him his very own Saga.

Grettir was lazy, somewhat stupid, mean to both animals and people, and a diligent murderer. Icelanders have forgotten these unfortunate traits, however, and prefer to talk about his strength and prowess.

So much is Grettir renowned for his superhuman strength, in fact, that if an enormous rock stands out of place somewhere in the Icelandic wilderness, it is said that Grettir Ásmundarsson carried it there. Such stones are called 'Grettistök' ('Grettir’s Burden').

The actual English name for 'Grettistök' is 'Glacial Erratic', and refers to a rock left behind after being moved out of place by a glacier. Perhaps this misconception encapsulates Grettir's enormous legacy—the legacy of a man who has been dead for more than a millennium.

- See also: Icelandic Literature for Beginners

As modernity rolled in, sailors and dockworkers became the new embodiments of pure strength, battling the cruel North Atlantic and carrying heavy barrels of herring around like empty pillow cases.

Geographically and culturally isolated, Icelanders lived in their own little bubble, sailing the unforgiving Atlantic and practising their Glíma, until a new darling entered the stage: powerlifter Skúli Óskarsson. As broad as he was tall (though he wasn’t particularly tall), Skúli became the first Icelander to break a weight lifting world record when he lifted 315.5 kilos in raw deadlift in 1980.

And oh how Icelanders loved their new hero; the world was finally forced to admit they were strong! Only four years later, Iceland burst onto the Strongman scene full force, adamant to claim back the Warrior and Viking glory of old.

The King of Strength: Jón Páll Sigmarsson

"I am the strongest! I am the Viking!" - Jón Páll

Jón Páll Sigmarsson, born in 1960, stepped into the Strongman scene with not only the strength of an ox but the speed of a cat and the personality of a true showman. Originally a bodybuilder, this larger-than-life personality won over the nation with a wide smile, light jokes and jests, and the ability to somehow turn strongman sports into an audience participatory game.

“Ekkert mál fyrir Jón Pál!”—“Ain’t no problem for Jón Páll!”—Icelandic six-year-olds would proclaim on 1980's playgrounds before attempting to do something monumentally challenging like climbing on top of a garage or trying to pull loose stone slabs from the street. There didn’t seem to be a single thing Jón Páll could not do.

First competing in World’s Strongest Man in 1983, he won the silver—a veritable achievement for a newcomer. The year after, he got the gold. The pride of a nation, Jón Páll was now known not only for having a way with the audience but also being a remarkable all-around athlete.

Strongmen competitions had been static for the most part, but Jón Páll brought with him what some would call a sailor’s swiftness, a demeanour and an attitude that forever changed the sport.

Jón Páll himself claimed to be the fastest Strongman in the world, but admitted that Bill Kazmaier, his competitor and Arch Rival (yes, with a Capital A), had the strongest feet. Still, Jón Páll won Kazmaier in a deadlift competition, where he performed a record breaking 532 kg (Approx 1173 lbs) deadlift, followed by the roar: “There is no reason to be alive if you can't do deadlift!”

Jón Páll was known for playing around while competing. One time, he took a moment to dance a little waltz with the Húsafell lifting stone to entertain the audience. On another occasion, when a heckler yelled for ‘The Eskimo to Hurry up!’ Jón Páll to yelled back “I’m not an Eskimo! I am a Viking!” before promptly lifting a 500kg carriage.

Jón Páll was the greatest Strongman of his time, and one of the greatest of all time. His short career landed him 16 championship titles, and 30 medallions in total, excluding the Icelandic titles he won. He won the title of World’s Strongest man four times and has his name engraved in the World’s Strongest Man Hall of Fame, along with three others.

But like many bright lights, Jón's burned out quickly. On January 16th, 1993, Jón Páll suffered cardiac arrest due to a traumatic aortic rupture which likely was a result of a congenital heart problem known in his family. The defect was probably aggravated by years of intense training and heavy strain of the constant monstrous weight lifting.

His legend inspired Icelanders for years to come and fully cemented power athletics as a part of the Icelandic national image. Jón Páll was a national hero and a near-saint in the eyes of his countrymen.

Jón Páll Sigmarsson died at the young age of 33, in his gym, doing what he loved most: the Deadlift.

Heir to the throne: Magnús Ver Magnússon

“...The trick is to have almost no weaknesses.” - Magnús Ver

Starting his career somewhat humbly, Magnús Ver came in as a ‘reserve competitor’ in World’s Strongest Man in 1991 after Jón Páll had to drop out due to injuries. He stayed humble for a total of five minutes before he went on and did what the Icelandic nation believed Jón Páll would do: he won. The funny thing? He wasn’t really focusing on being a strongman at that point.

Magnús was young and vibrant, the Kid in the Competition, the Pretty Boy, and possibly even faster and more agile than his predecessor. Later times have hailed him as one of the most technical strongmen in history, combining Jón Páll’s system of athletics and explosive speed with an impressive static strength that allowed him to outlift many professional powerlifters. He even out lifted the famed O.D. Wilson and was hailed as a phenomenal lifter for his weight class.

Magnús Ver went on to win the World’s Strongest Man competition three more times, matching Jón Páll’s record of four championships won. He dominated the 90’s as Jón Páll had dominated the 80’s before him, even though he was considered ‘somewhat smaller’ than the average Strongman at 1.9m and 130kg (6’3 ft and 290 lbs).

Magnús Ver might not have been the showman Jón Páll was, but he too was quick to smile and laugh, upholding the good-natured giant stereotype that Icelandic Strongmen had started to represent. They were big and strong and knew it, and they had nothing to prove—especially the farm boys from the east fjords, they’d already done their ‘proved’ themselves during one fishing season or another.

Magnús Ver’s legacy is more entwined with the Strongmen of the future than any before him, as he took over Jón Páll’s gym after his death and still runs it today. The name is different from the original Gym 80, though. Now, it’s a known place, a veritable Nest of Giants and a mecca for all strongmen visiting Iceland: Jakaból

Of course, a strongman-oriented gym, built by a strongman for other strongmen, is no ordinary treadmill-kettlebells-yoga mattress studio. Most of the equipment is raw concrete and steel, crafted by Magnús Ver himself.

Jakaból gym is located in in the middle of the Breiðholt district, surrounded by apartment buildings, in an unassuming, single-storey house behind a convenience store, marked with a single, small sign.

At 54 years of age, Magnús Ver does not compete anymore, but he still judges internationally and trains world class strongmen. He lives in Reykjavík and can still bench press his own body weight with ease.

The Quiet Years

For thirteen years in a row, Icelanders took home medallions from World’s Strongest Man competitions, eight of them being gold. Second only to the United States, Iceland has won a total of 19 medallions overall.

After Magnús Ver stopped competing internationally, Iceland had many strongmen, but none of them came close to the calibre of Jón Páll and his successor. Great strongmen, such as Hjalti ‘Úrsus’ Árnason and Torfi ‘Loðfíllinn’ Ólafsson had an honourable run, though medallions in the World's Strongest Man were seemingly out of reach.

Little by little, the Giants and powerlifters that formed the army of Icelandic strongmen started giving way to other athletes. Direct broadcasts stopped, and events like Vestfjarðavíkingurinn ('The Viking of the Westfjords'), a local Icelandic competition, lost their prime time location and were wedged between news commentaries and Sunday morning cartoons.

Fitness forms for the more average body type began to take over. Crossfit competitions increased in popularity, and, with the entrance of Gunnar Nelson, mixed martial arts started gaining traction. And then, of course, the country's love for football was on the rise.

The strongmen were getting old fashioned and were traded out for more dynamic sportsmen. However, deep within the hearts of the people, all athletic victories were bound to the strength and prowess that was connected to the legacy of the Vikings, cemented by the reign of Jón Páll.

Strength had become integral to the Icelandic national identity—we were small, but we were the strongest. Maybe it had something to do with the ‘character’ and charisma of many Strongmen in the country. They were personalities and entertainers, just as much as athletes, and the people loved them, not only for their strength but for the image they upheld: heroes who were bright and bold, kind and joyfully spirited.

Gradually, the sport faded away, though as a token of a bygone golden era, the Icelandic strongmen were still mentioned in the sports sections. Until, of course, the Mountain arose.

The New Era: the Mountain Rides in

Once upon a time, there was rather skinny but very tall kid who played basketball. Then, he got injured and couldn’t play anymore. So he started lifting heavy things. He remained very tall. He did not, however, remain very skinny.

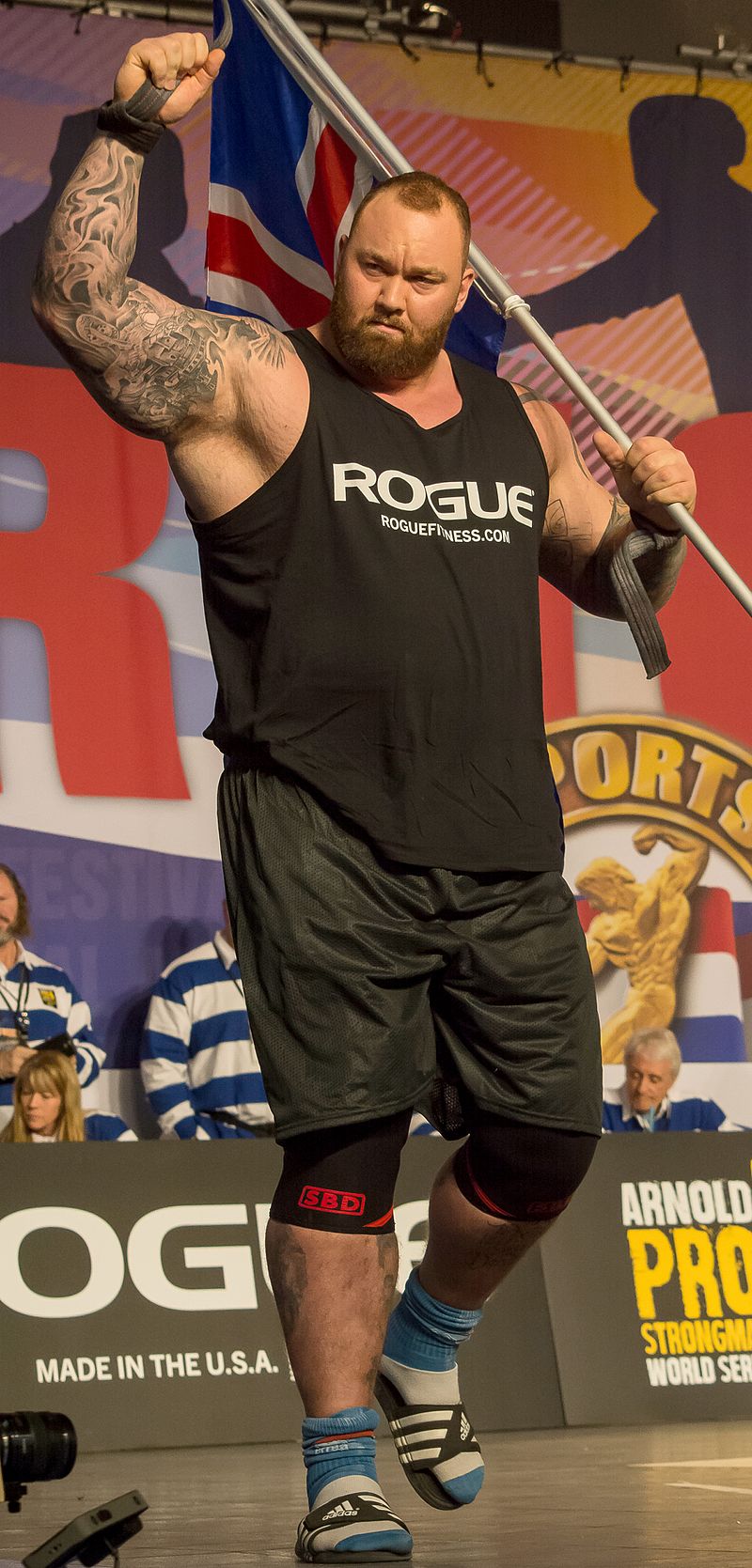

Hafþór Júlíus Björnsson (anglicised as Hafthor Bjornsson), entered the strongman scene in 2008 under the guidance of Magnús Ver when he started training at Jakaból gym. A year later he started competing in Powersports. At 206cm (6’9 ft) and averaging at 110kg (240 lbs) with a highest listed weight around 200kg (440 lbs), Hafþór Björn is enormous, even for a strongman.

His size alone has made him dominant in Icelandic strongman competitions, though, for a time, he had some struggle breaking into the legendary status of Jón Páll or Magnús Ver. Thankfully, as of 2018, Hafþór Júlíus has succeeded in achieving these new heights, officially winning the world's strongest man competition.

This, as the title clearly implies, means he is the strongest man in the world.

Even if, somehow, such an iconic title had still managed to elude him, he has plenty of titles to boast over—one being the world champion in keg tossing (7.15 m). More importantly, he is the only living man who has broken a Saga-era record, by carrying the 640 kg (1411 lbs) mast of the Viking longship Ormurinn Langi for five whole steps, breaking the 1000-year-old record of Ormur Stórólfsson.

According to legend, forty men lifted the mast to Ormur's shoulders, and he took three steps before breaking his back and falling to the ground. Hafþór, however, took five steps, never fell, and his back was fine.

Hafþór may even be better known than both Jón Páll and Magnús Ver combined. Hollywood had use for a man of Hafþór’s size and in 2013 he was the third person to take on the role of Gregor Clegane, nicknamed ‘The Mountain’, in the HBO series Game of Thrones.

Two actors had taken on the role before him, but due to scheduling conflicts the show needed a new Mountain, and they needed it fast. Thankfully they were filming in Iceland at that moment, where Giants are locally grown at a small gym in Breiðholt.

At that time, Hafþór had already won two bronze medals in the World’s Strongest Man competition, and numerous other titles. Even though he was shorter than his acting predecessors, his sheer bulk more than made up for the missing inches.

The entrance of Hafþór into the international entertainment scene prompted Icelander's to turn their heads from football games for a moment. A small, but proud nation directed its gaze to the next possible world conqueror. After all, Icelanders like whoever is reminding the world that they might be few, but that they are awesome anyway.

Hafþór became a household name overnight and opened his own private Strongman gym—which, of course, is locatedin an industrial district with one small sign.

Hafþór has had a more turbulent relationship with the press than his predecessors. Initially, this was due to the very different environment that he has had to deal with in the day and age of social media and instant news.

The Strongman scene is also vastly different, and no longer do TV broadcasts have segments of all competitors chilling in the hot tubs together, good-naturedly poking fun at each other. He lives in a harder, colder world of clean professionalism, agents and media appearances.

At the moment, Hafþór has pulled out of acting for the time being as he is focusing on his strongman career. That means full-time eating and working out, full time hitting the concrete slabs and, more importantly, winning the mental battle that follows lifting inhuman amounts of weight.

Iceland's Strongmen of Today

Even in Iceland, a country lauded for being a natural breeding ground for people genetically predisposed for Powerathletics, the strongmen sport is not without contoversy. As a nation who lost a bright star early, people are all-too aware of the potential dangers of overworking one's body to reach the god-like strength of the Viking sagas.

The debate of growth hormones and steroids never goes away, but perhaps the dietary insanity that goes hand in hand with the strongmen workouts is the most daunting aspect of their life styles; when preparing for competition, Hafþór, for example, eats eleven (yes, ELEVEN) meals per day to maintain his bulk and feed his muscles. That does not include the added fruit juice that he drinks constantly to ‘get more calories’.

A brief look at his contest preparation dietary plan exposes an astronomical daily food intake that includes 14 eggs and 2kg of meat and fish.

Ther is also the newfound complication of fame outside the sport. During the times of Jón Páll and Magnús Ver they were strongmen first and foremost, and only occasionally appeared in advertisements based on the fact that they were the World’s Strongest Men.

Hafþór's fame, however, stems from show business, and his public image is interlinked with his Game of Thrones persona, Gregor Clegane—to the extent that he has simply become known as The Mountain.

He has also launched his own products, ranging from sports gear to alcohol, with nearly all of them either pointing to or directly citing his place in show business, rather than his standing as a strongman. But then again, a man has got to eat, and in Hafþór’s case, his grocery bill extends well beyond the realm of the ridiculous.

The intense competition seems to have turned the outward appearance of the life of a modern day strong man to a hard world, where there is little room for jokes or fun. Certainly none seem to be taking the role of the Showman or the New Blue Eyes, like Jón Páll and Magnús Ver. Hafþór lives in a vastly different world, where not only the no-jokes competition but the lure of commercial value has gained a larger foothold than before.

Still, it does not change much. The sport is still the sport. The commercials, the TV shows and film contracts will never take the heart out of the competition, which demands total dedication of its practitioners, every hour, every day. It matters little if you are a film star, a gym owner, sales representative or a high school teacher. It demands sacrifices in the form of overworked bodies on the edge of godhood—and a promise of a place among the worthy, as has been told in Icelandic stories for as long as the nation remembers.

Whatever they say, you need strength to be strong. We might not need fishermen who can lift the Fullsterkur stones anymore, but many locals still turn to the inherent value of the strength as a representation of an enduring spirit. Maybe it was never really about strength in the form we see today, but the toughness needed to reach it. For, as they say; Tough times never last, but tough people do.