The story of the Icelandic flag is, in many respects, the story of the Icelandic people; it is a testament to their struggle for national identity, for cultural independence and their long commitment to Iceland’s future. Wherever the flag of Iceland flies, it exemplifies that struggle as well as the staggering achievements that have since been accomplished by this young nation, be it in the arts, sports or political arena.

Photo above from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Árni Dagur, and Magasjukur2. No edits made.

Why You Can Trust Our Content

Guide to Iceland is the most trusted travel platform in Iceland, helping millions of visitors each year. All our content is written and reviewed by local experts who are deeply familiar with Iceland. You can count on us for accurate, up-to-date, and trustworthy travel advice.

- Interested in history? See International Relations in Iceland

- Experience the culture with this Hop On - Hop Off City Sightseeing Tour

- Save money with the Reykjavik City Card

Visitors to Iceland will encounter the flag almost everywhere they go: on football shirts, woven into souvenir pillows, flying outside churches and hotels and government buildings. One might be forgiven for considering this a touch isolationist, but then, this lonely and distant island has, by default, forever been so.

But is this the same vision of exceptionalism so popular with our American cousins? Or is it a tourist culture now running amok, turning the Icelandic standard into a novelty item? Icelanders are quick to sport their national colours, dressing their city and themselves with the red, white and blue of this burgeoning young nation.

You see, quite unlike most flags that have been waved over the years, Iceland’s flag cannot be junctured alongside a cruel colonial history, nor has it been hijacked by hard right-wingers or ever been considered roundly as a symbol of overarching authority. In that sense, the symbolism associated with the flag is pre-pubescent and lacking negative connotation.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Bjarki Sigursveinsson. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Bjarki Sigursveinsson. No edits made.

In fact, Icelanders tend to see their flag on the contrary—the fight for Iceland’s flag played an important part in the country’s independence from Denmark and thus is considered something of a trophy.

Having long been influenced or directly controlled by Norway (and later Denmark,) the will for autonomy has always been an inherently Icelandic characteristic and can be traced back to the country's first settlers, who in their own way, escaped the established rules of Scandinavia in a bid for a better, freer life.

Icelandic patriotism is something entirely new unto itself; fed into by the country's gorgeous and untarnished nature, as well as their cultural and economic focus on tourism, patriotism here has taken the form of celebrating the existence of one's country itself, rather than one's illusory feelings of superiority. Patriotism is referred to in Icelandic as Þjóðernishyggja ("nation-mindedness") or Föðurlandsást ("Love of one's country").

That's not to suggest that Iceland is devoid of its share of far-righters—thankfully, it is a small minority group, adherents to Þjóðernissósíalismi ("National Socialism"). But pride here is derived from a community spirit and cultural revolution; rather than a historical legacy, the Icelandic flag represents the republic as it is.

Iceland has twelve flag-day public holidays, a sure reminder of just how important an appreciation of the state is to Icelanders.

Ideas of Icelandic nationalism are based on the values of the Icelandic Free State, otherwise referred to as the Icelandic Commonwealth; freedom for the individual, independence, the preservation of language, democracy and respect for religious and customary traditions.

Icelanders today believe the current republic is, in many respects, a reincarnation of that Commonwealth; the flag itself is emblematic of that vision, a red-white-blue tapestry that reveals both a deep connection to nature and to local roots.

But, given Iceland's centuries-long struggle for independence, how did this small, sub-Arctic isle finally break away from its colonial masters to sculpt and formalise its own identity? How has the flag changed over the years, and has it changed to reflect the values of the Icelandic people? And, considering proposals to, once again, redesign the states' banner, is this tale of identity truly over?

History of the Icelandic Flag

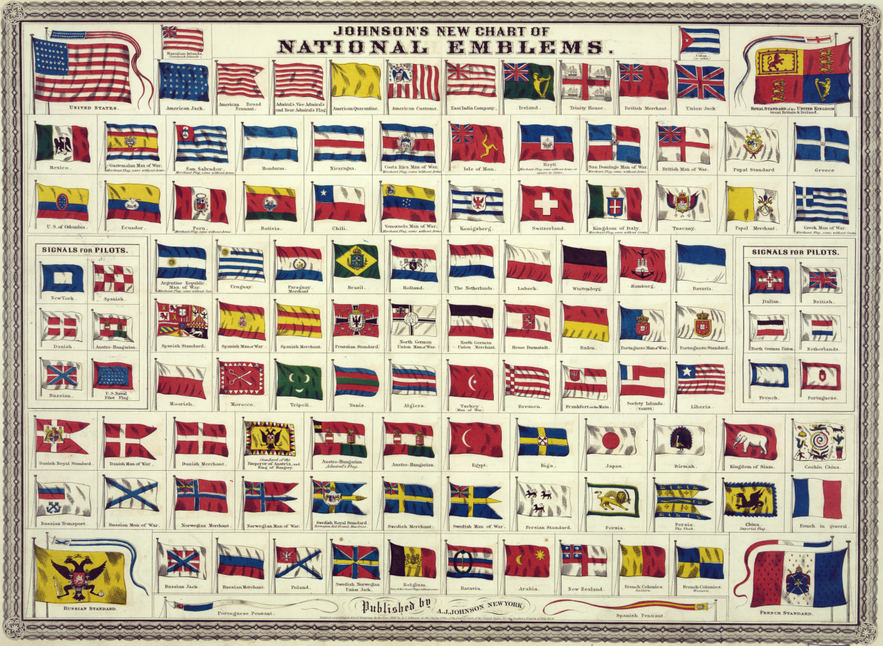

Historically, flags were used on the battlefield to identify warring factions. Often they were utilised as field markers, or as a means of recognising heraldic status—who and who wasn't a knight, for instance. It wasn't until the Age of Sail (corresponding roughly to mid-16th to mid 19th century) when flags were used by trade and naval vessels to display 'their national colours'.

They were also used as a vital means of communication between ships, resulting in what would later become the International Code of Signals. Over time, these maritime flags would develop into the national flags we know today.

- See also: The Most Infamous Icelanders in History

The rise of nationalism in the 18th century was also inherently linked to the development of flag use. The widespread, societal use of flags, national songs, symbols on money and patriotic clubs build a sense of belonging and togetherness to a community.

By representing ourselves under a singular banner, our sense of duty to the group is implied as, inherently, making up an important aspect of one's singular identity.

Given that Iceland did not achieve independence until the mid-twentieth century (in 1944), a national flag was never on the cards throughout the majority of the country’s inhabitance. And yet, given Iceland's sea-based economy, flying flags from fishing vessels was imperative to trade. Due to Denmark rule over Iceland, the Danish flag was flown by Icelandic vessels, a sultry reminder of the people's imperial overlords.

The Danish flag (known as the "Dannebrog") is the oldest attested flag still in use today. Dating back to 1478, it is said that the flag was handed down to the Danish people by God himself following their victory against the ancient states of Estonia in the Battle of Valdemar.

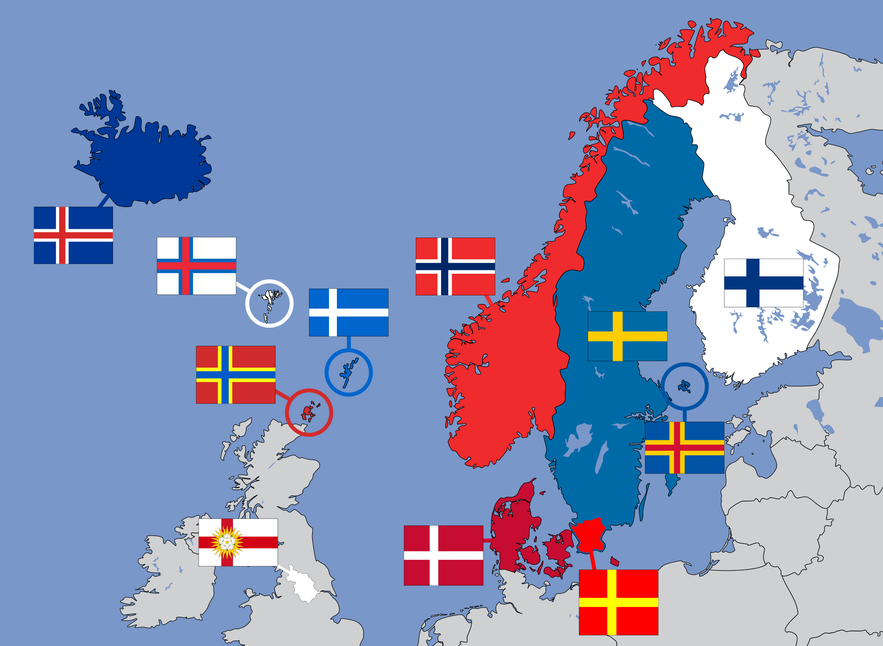

Naturally, the Nordic Cross design represents the Christian heritage of Scandinavia and is one of the oldest known symbols to man; nations have used the cross in their flag designs eclectically, from the St. George's cross, where each quarter is of each size, to the Nordic Cross, where the centre of the cross is shifted to the left.

The flag was then used in the Nordic countries within Denmark's influence—eg; Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Finland—later serving as an inspiration upon each country's independence. The Nordic Cross has inspired flags outside of Scandinavia too. British Islands such as the Shetlands, Orkney and Barra all use the Nordic Cross, as do city flags in Brazil, Latvia, Estonia and the Netherlands.

Jørgen Jørgensen | 'The Dog Days King'

Jørgen Jørgensen, a famed Danish explorer in the Age of Revolution, played an early and unexpected role in the developing history of Iceland’s flag. Ever since he has held a special place in the nation’s heart as one of the more colourful characters to have traipsed this aged isle. Full of ambition, spirit and a courage that often usurped his wayward moral compass, the English-Australian novelist Marcus Clarke referred to him as “the human comet”.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg. No edits made.

How Jørgen came to be known as ‘The Dog Days King’ in Iceland begins with a point in history; the Action of 2 March 1808. Jørgen was captaining the 28-gun Danish brig, Admiral Juul, when it exchanged cannon fire with the 18-gun, British-owned ship, HMS Sappho. With barely any loss of life (two casualties on the British side), the Admiral Juul was commandeered, its captain hurriedly arrested.

Given the man's persuasive nature, Jørgen’s British captives conceded that the erratic adventurer could be best utilised as a privateer. In the next year, whilst on parole, they dutifully returned command of the Admiral Juul to him; it was then that Jørgen, alongside a rag-tag group of English sailors, decided upon a mercantile mission to Iceland. Given that Iceland was experiencing food shortages at that time—a by-product of the Danish trade monopoly—Jørgen instinctively assumed that trading there would be profitable.

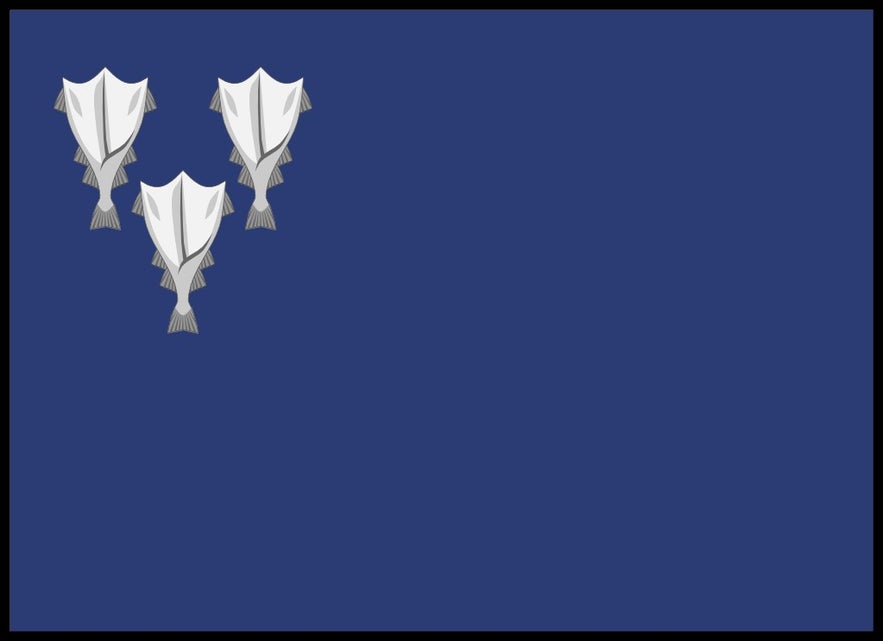

In 1807, Jørgen arrived on the shores of Iceland. After being refused the right to trade, Jørgen and his men quickly arrested the Danish governor of Iceland, Frederich Christopher Trampe. Jørgen held deep ambitions to revolutionise Iceland as a liberal republic, reminiscent of those societies emerging in Europe and North America. Within a matter of days, he declared himself the de facto ruler and ‘Protector’ of Iceland, declaring the country’s independence from Denmark and hoisting Iceland’s first known flag.

According to Jørgen’s directive, Iceland’s flag would be blue (the then perceived national colour of Iceland), with three stock fishes in the upper left-hand quarter. The inclusion of three stockfish on the flag is a clear indicator of Iceland’s relevance to the larger empires as a profitable fishing base. Icelanders have forever found this humiliating and, when the moment first arose, they moved to change the stock fish to a falcon, widely regarded to be a more traditionally Icelandic symbol.

As for Jørgen, his rule over Iceland was short-lived and largely uninfluential. For nine weeks, Jørgen held dominion over the island, having constructed a defensive fort manned by unqualified drunks and farmers. And yet, his time as usurper ended quietly upon the arrival of the HMS Talbot. Of his own accord, Jørgen returned to the United Kingdom.

The remainder of his life would be a fluctuation between exploration and gambling—he was finally exiled to Tasmania as a convict, where again, he managed to live the life of a relatively free man. Today, a bridge in Tasmania shows the carved head of Jørgen, adorned with the crown he never quite earned.

Sigurdur Gudmundsson

In 1870, a new flag design was proposed by the Icelandic artist, Sigurður Guðmundsson. Again, the flag had a blue background, but this time introduced the white falcon as the flag’s centrepiece.

This particular design is of note due to the local Icelandic government's proposition to the Danish monarchy that changes be made to the nation's crest. The falcon was considered a more noble animal than a split cod, whilst the open wings were to symbolise a nation ready to take a flight; a visual and, seemingly despondent metaphor for the Icelandic people's will towards independence.

Interestingly enough, the Danish monarchy agreed to change the crest, though when it came down to designing it, there was one immediate hiccup. According to urban legend, the Danish artist commissioned to illustrate the new crest closely followed the aesthetics and dimensions of a taxidermy falcon. The only problem was that this falcon was posed sitting with its wings firmly closed. One cannot be sure if this story is true or not, but it does indicate Denmark's reluctance to see Iceland's independence take flight.

This flag design was particularly popular amongst politically-active students and, in 1874, during Iceland's 1000 year anniversary of the settlement, it was the most widely flown design.

Einar Benediktsson

One man who felt the flag design improper was the poet, Einar Benediktsson. On 13th March 1897, Einar wrote a published letter in his journal Dagskrá claiming that the falcon-flag neither followed an international pattern nor did it truly represent Iceland as a nation. In the proceeding years since Sigurður's 1870 design, the independence movement was once again gaining traction; Iceland's attitude toward self-governance was, day by day, undermining Denmark's insistence that the island needed them.

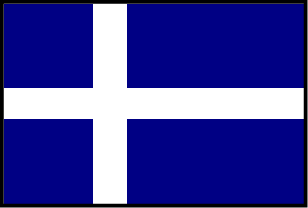

In the Falcon flag's place, Einar proposed the above design, a white Nordic Cross on a dark blue background, claiming it was the most convenient. Unfortunately, the flag was almost identical to the then Greek national flag, and therefore the Danish monarch refused to sign off on the proposal.

The Danish monarchy and the Greek monarchy long had connections through family—the majority of the deposed Greek dynasty was in fact referred to as Prince or Princess of Greece and Denmark. There was also some concern that, in stormy weather, the flag might be confused for the Swedish flag—almost identical, save the cross is yellow, rather than white.

Interestingly enough, this flag design is almost identical to the flag of the Shetland Islands, the only difference being the shade of blue used.

1914 Flag Committee Proposal

In 1914, having had his proposals rejected by Denmark, the Prime Minister of Iceland, Hannes Hafstein, returned home to, once again, attempt another proposal. Allowing Denmark to simply forget about the matter of an independent flag was never on the agenda. The Prime Minister set up a committee “to consider in detail the design of the flag, establish as far as possible the nation's wishes and present proposals to the government on the shape and colour early enough to give Parliament, when it next convenes, the opportunity to deliver an opinion on it.”

The committee was typically Icelandic, comprised of a variety of disciplines which included: the chairman, Surgeon General, Guðmundur Björnsson, the keeper of National Antiquities, Matthías Þórðarson, the academic Jón Jónsson Aðils, the newspaper editor Ólafur Björnsson and a painter, Þórarinn B. Þorláksson.

As per the Prime Minister's instructions, the committee asked the Icelandic public to send in their own designs for a new flag. The panel received 46 designs back, the vast majority of which included a Nordic Cross as the centrepiece (two designs heavily featured Mjölnir, the hammer of Thor.) 13 of the 35 Nordic Cross designs specified the colours red, white and blue.

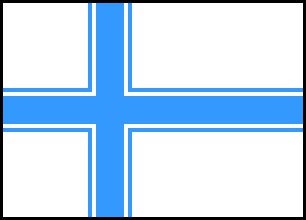

White and blue have long been considered the national colours of Iceland, a thought clearly on the minds of the 1913 government committee enlisted to design Iceland's flag. The committee finalised on two different designs; first, the above flag (white background, sky blue cross), and second, a design that closely resembles the flag today.

According to documents from the time, the Prime Minister was certain that the Danish King would ratify one of the designs. Little did he know that no formal ratification would come until two successive Prime Ministers left.

Matthías Þórðarson

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Smooth_O. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Smooth_O. No edits made.

Many today consider the flag’s colour scheme to be representative of Iceland’s physical qualities; this concept, in fact, originated in 1906 with a man named Matthías Þórðarson. Matthías proposed his flag design to the Reykjavík Student’s Association, taking the time to point out what each colour meant; the red cross was an allusion to the lava and fire of Iceland’s geology, the white cross signifying the snow and the blue background denoting the Atlantic Ocean.

Over the next decade, Matthías’ flag slowly came to be considered the government’s favoured prototype, quite in contrast to the population’s choice, who considered Einar Benediktsson’s design more preferable.

Loyalty for Einar's design was heightened following an incident in 1913; during a rowing competition at Reykjavik Harbour, a Danish warship felt it necessary to confiscate the flag from flying atop one of the boats, quickly stirring a political controversy.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Andreas Tille. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Andreas Tille. No edits made.

By 1915, the issue of the flag was, once again, on the table. The new Prime Minister of Iceland, Jón Magnússon, set it as a priority to reevaluate the relationship between Iceland and Denmark 'in its entirety.' Many, especially in Denmark, thought that negotiations of this kind were inappropriate given that World War One was still raging across Europe.

Having had his proposals unanimously passed by the Icelandic parliament, the Prime Minister was to be disappointed once again at Denmark's refusal to ratify a maritime flag. There was a silver lining, however; both the Danish government and monarch conceded that they were willing to renegotiate the terms of Iceland's legislative and executive processes. Spurred on, the Prime Minister refused to resign, returning to Iceland more determined towards his ambitions.

Things took a turn for the better in the summer of 1918 at the behest of the new Danish-Icelandic committee. By November, both parties had passed the Act of the Union legislation, a law that stipulated Icelandic vessels could fly no other maritime flag but their own—it was Matthías Þórðarson's design that took that honour. Denmark made it clear however that Icelanders were to fly their own flag beside the Danish standard, not independently from it.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Christoph Strässler. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Christoph Strässler. No edits made.

And so, in December of that year, flagpoles were erected to hang from Government House. In place of the Prime Minister, who was in Copenhagen at the time, the Finance Minister, Sigurður Eggerz spoke out to crowds of Icelandic people;

“Yesterday the king issued a decree on the national flag of Iceland, which as of today will fly above the Icelandic state ... The flag is the symbol of our sovereignty. The flag embodies the most beautiful ideals of our nation, every achievement made by us, enhances the value of the flag, whether at sea in battle with the surf and rough waves, in industrial development or in the sciences and fine arts. The more noble our nation, the more noble our flag. Its honour and renown is the fame of our nation..."

The ceremony was marked with a 21-gun salute and a number of speeches. Interestingly enough, Iceland had for the first time hoisted its own flag, despite not having completed the provisions for it. The occasion was ended with the Danish and Icelandic national anthems.

1918 saw the closure of the first World War; having devastated and depleted the mainland European powers, the power of balance had irreversibly shifted from the influence and control of colonial foreign policy.

Denmark had maintained a difficult neutrality throughout the war, but upon it being obvious that an Allied victory was forthcoming, the nation was acutely aware that to bargain with the allies they would have to loosen their grip on the foreign territories under their jurisdiction. Many in the Danish government at that time were positive towards giving Iceland more autonomy.

Sovereignties to Denmark were cut forever after the latter fell after six hours to Germany's invasion force during the Second World War. In the period between both World Wars, Iceland's thirst for independence had developed dramatically into a fully fledged, populace-backed movement. I

n 1944, a vote was held following the 25-year expiration of the Act of the Union. Parliament voted overwhelmingly in favour of abolishing the Danish monarchy, and thus, the Republic of Iceland was established 17 June 1944.

The Second World War brought its own challenges to Iceland's newfound independence, however. In order to deny Germany the chance to invade Iceland (its position between mainland Europe and the US is strategically crucial), British forces invaded on 10 May 1940. They would later hand over their role to the Americans. As can be imagined, with the construction of the US air base in Keflavik, discussions around Icelandic independence would continue long into the century.

Future of the Flag?

Over recent years, there has been some interest as to redesigning the Icelandic flag completely. In 2014, for DesignMarch, a nostalgic call out to the public was made for new flag proposal, celebrating the hundred years since the historic flag committee.

Hörður Lárusson—an instructor at the Icelandic Academy of Arts, as well as President of the Icelandic Association of Graphic Designers—was at the forefront of that campaign, dedicating much of his time (and studio space) to constantly reimagining Iceland's national flag.

An expert on the subject, he has also written two books, '“Fáninn / The Flag”' (Icelandic & English translations) and 'Þjóðfáni Íslands/The National Flag of Iceland' (Icelandic only).

Because Iceland received its national flag at such a late point in history, the symbolism behind the design could be argued as less authentically representative of Iceland and the Icelandic people. After all, the Nordic Cross, though culturally significant in its link to Scandinavia, tells only half the story of this country's development, and does little to differentiate it.

- See also: History of Iceland

Considering that Iceland's development, culture and tradition have grown independently of mainland Scandinavia, to hold on so rigidly to these links is tenuous at best. One potential change proposed is to do away with the Nordic Cross. Despite the shared union between Scandinavian countries and their flags, the concept of promoting a Christian heritage has started to fall by the wayside, making less and less sense in an era of modern technology and new age spirituality.

Other Flags Found in Iceland

Below I have chosen to include a variety of different flags that might be found in or around Iceland. Given that Iceland is comprised of, in total, 3 regions, 8 divisions and 79 municipalities, there are an enormous wealth of flag designs and crests that nod to the local identity of the people living there.

Considering the sheer number of municipalities, I have included only a small number of designs, though the full list of flags can be found here.

The Flag of Reykjavík

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, photo by Benedikt Thorolfsson. No edits made.

Also serving as the city's coat of arms, the shield centrepiece alludes to the story of Iceland's settlement. Iceland's first permanent settler, Ingólfur Arnarson, left his home in Norway after instigating a blood feud. In traditional Viking fashion, he let loose two logs into the water, following them until they washed up onto the shore. This was where Ingólfur decided to settle; today, that place is Iceland's capital city.

The Flag of Akureyri

Emblazoned against the Eagle is a small crest that shows a bundle of wheat. This is due to Akureyri's fertile surrounding landscape and the agricultural production that followed in the late 1800s. Fishing and tourism have since become the dominant industry sectors in the region. The crest is notably heraldic, in stark contrast to the fairly modern design of other municipalities' flags.

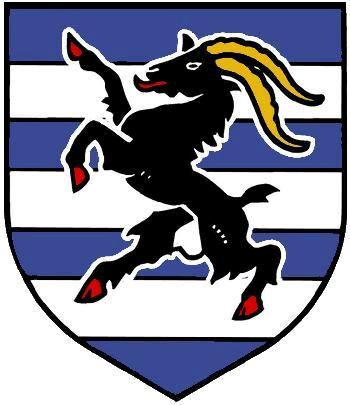

The Flag of Grindavik

In heraldry, goats are often used as a symbol for political ability, though in Grindavík's case, the reasoning behind it as a centrepiece is somewhat more mysterious. Grindavík has a long history as an Icelandic settlement, though its largest contribution to the country has always been in the fishing sector. One can however easily notice the white and blue national colours as a shield background.

The Flag of Hafnarfjordur

Hafnarfjörður's emblem is the Old Lighthouse, found on the hill off Vitastígur street in town. The lighthouse opened in 1901 but is now inactive, though visitors can still inspect it from the outside. The lighthouse is instantly recognisable; rectangular in shape, rather than smoothed, it is painted with red and white stripes.

The Flag of Isafjardarbaer

This flag and crest were designed in 1966 by Icelandic artist, Halldór Pétursson, and later updated by Pétur Halldórsson in 2011. The design shows two mountains of the Westfjords, with a ship sailing on a stretch of water in between them. The red circle signifies the midnight sun whilst the ship's mast is reminiscent of a Christian cross, and thus, an illusory nod to Iceland's adopted religious heritage.

The Flag of Stykkisholmur

Stykkishólmur's history lies predominantly in trading, long before the 16th Danish Trade Monopoly even. The township celebrates their historic routes with Denmark with an annual festival, "Danish Days". The flag's design appears to show a rotor, a possible nod to the town's secondary sector, fishing. The shape at the top is inspired by the small island, Stykkið, located just off the town's shoreline.

The Flag of Kopavogur

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Connormah. No edits made.

The flag of Kopavogur displays a green shield showing the town's famous church, Kópavogskirkja, focusing particularly on the building's peculiar, arched architecture. Below the church is an illustration of a young seal pup, in honour of one of Iceland's most famous resident species. The name of the town, in fact, translates to "Seal Pup Bay".

The Flag of Vestmannaeyjar

In accordance with the region's long cultural ties with the ocean, the Westman Islands' flag dutifully portrays a ship displaying two standards. Excusing for a moment, once again, the blue and white colours so typical of Icelandic emblems, the left-most flag appears to be either an early flag proposal (perhaps Einar Benediktsson) or, alternatively, the Danish national flag.

The Flag of Rockall

Something of an odd one this—in truth, I've included it only for the sake of curiosity. Rockall is a minuscule and uninhabitable islet smack in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. Sovereign rights over this piece of land means a greater stretch of territorial water, meaning that the question as to who owns Rockall Island is a politically heated one.

Let's not forget, the dramatic, yet bloodless Cod Wars occurred over just as much. Ownership of the island is disputed between the United Kingdom (who have planted the above flag), Iceland, Ireland and Denmark.