Which historical Icelanders were the most notorious? What impact did they have and how did their mischiefs shape what is now considered the most peaceful of nations? Read on to learn about these fascinating individuals, their heinous crimes and vagabond lives, on our list of the most infamous Icelanders of history.

- Read about more infamous Icelanders in the History of Iceland

- Find out more about the people of Iceland in the History of Reykjavík

- Learn about the Top 9 Most Famous Icelanders in History

Iceland is by many considered to be a peaceful place, free of serious crime and bloody conflict. In 2017, the country even topped the Global Peace Index (GPI) report for the tenth consecutive year in a row.

Why You Can Trust Our Content

Guide to Iceland is the most trusted travel platform in Iceland, helping millions of visitors each year. All our content is written and reviewed by local experts who are deeply familiar with Iceland. You can count on us for accurate, up-to-date, and trustworthy travel advice.

But if you take a close look at the country's history, you might find that such accolades aren’t entirely telling of the bygone times that shaped the Icelandic nation.

Recently, we published an article on the famous Icelanders who had the greatest impact on our culture and our history. The island of ice and fire has indeed generated many fascinating individuals, dating all the way back to its early settlers. The available Icelandic sagas give us incredible insight into an age long gone, full of heroes and explorers—but what of the villains and sinners?

We thought it high time to compose a list, not of Iceland’s best but worst - of daring outlaws, vicious Vikings, legendary bandits and murderous savages.

Which of those historical Icelanders stood out as being particularly vile? Which tales are the most shocking? What notorious ancestors are most remembered by the Icelandic people today, and what were they so notorious for?

Egill Skallagrimsson

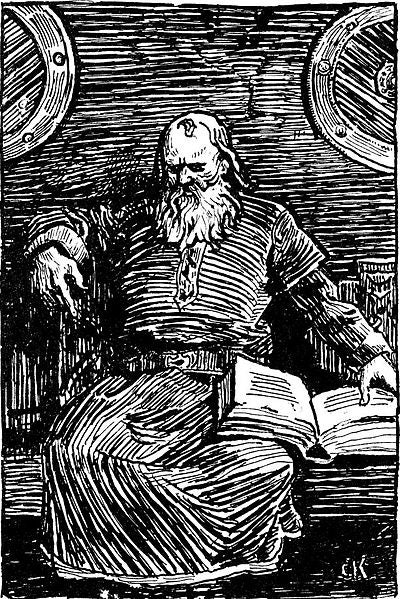

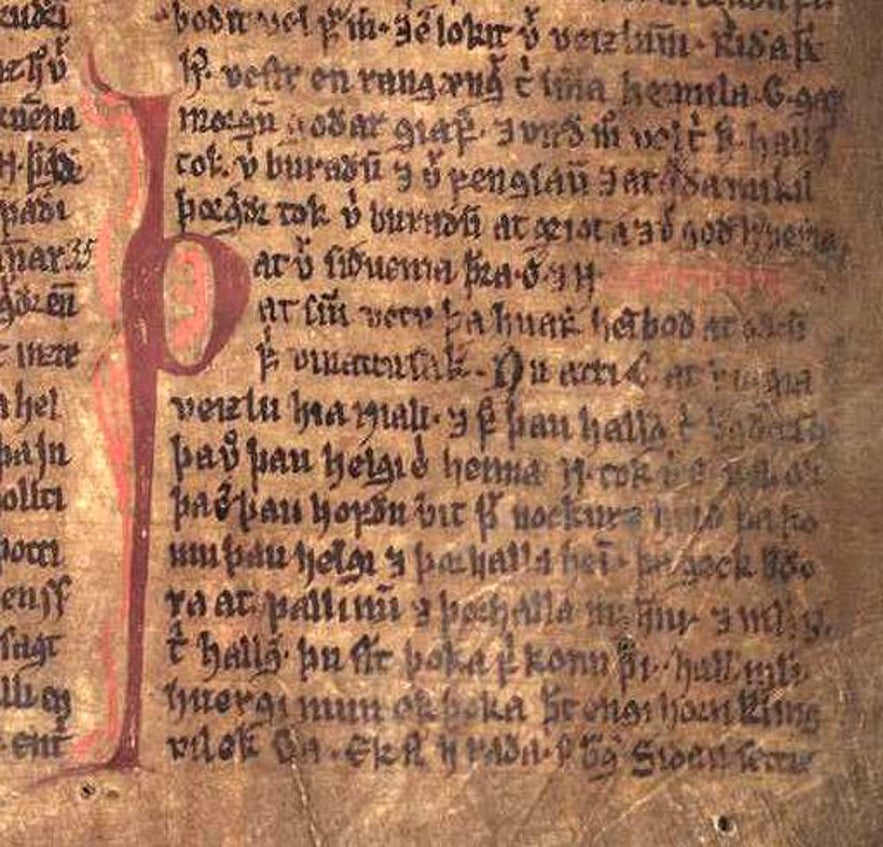

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Árni Magnússon Institute in Iceland. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Árni Magnússon Institute in Iceland. No edits made.

We'll begin our list with the household name of Egill Skallagrímsson, a Viking-Age warrior and poet, infamous for having first killed a man when he was only seven years old.

Apparently, this was not such a big deal at the time, at least not in the same way as it would be today. In fact, Egill's mother complimented him, proclaiming that he had the means of becoming a great Viking.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Oscar Arnold Wergeland. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Oscar Arnold Wergeland. No edits made.

Let's remember that the word “Viking” did not always have the meaning it has today. Throughout the Viking age, it was used to describe Scandinavian Norsemen who explored and raided Europe by sea.

Today, the word is used as an umbrella term for every Scandinavian man of the Viking-Age—the period from the late 8th century to the mid 11th century—most of whom were farmers by profession, and therefore not occupied with Viking endeavours all the time.

So when Egill's mother said that her son should be a Viking, she was referring to his skills as a warrior and a killer. Throughout most of his life, Egill would be prone to outbursts of violence, eventually gaining the repetition of a Berserker.

Egill is estimated to have been born in the year 910 in the farmstead Borg in Mýrar, just west of the town of Borgarnes. Since Iceland's Age of settlement was between 870-930 AD, Egill Skallagrímsson belongs to the first generation of Icelanders.

- See also: Where Did Icelanders Come From?

- Explore the homeland of Egill Skallagrímsson on this Borgarfjörður and Langjökull Glacier Tour

He is considered a true embodiment of the Viking-Age, where a man's value resided in his sword, his word, his spirit and his bravery. From an early age, Egill fought great battles and served as a mercenary for mighty kings. His entire life was, in fact, to a great extent plagued by conflicts against the Norwegian Crown, who continuously denied him his claims to his inheritance.

Egill was never one for being scorned; his first kill, in fact, was a murder of a boy who cheated him in a game of ice-hockey. And later, when Bárður of Atley, a retainer of King Erik Bloodaxe of Norway, gravely insulted Egill, he killed him for it. The king and queen consequently devoted their lives trying to take vengeance, sending the queen's two brothers to slay Egill for his crime.

But Egill killed them both, which lead King Erik to outlaw him from Norway. The bloody feud continued, peaking when Egill slew the king's son Rögnvaldur. Consequently, Egill presented himself to the king to plead for pardon.

The king decided to postpone Egill's execution until the next morning, so he stayed up all night composing a lengthy and exceptional 'Drápa' (a form of skaldic poetry). The story goes that his poetry was so extraordinary, that it convinced the king to pardon his own son's murderer. Egill's greatest feat, therefore, was not achieved by means of sword and axe, but his words and wits.

Most of our knowledge of Egill Skallagrímsson's life comes from Egil's Saga; a manuscript believed to have been written by Snorri Sturluson. Its oldest fragment dates back to 1240 AD, about 300 years after most of its events are said to have taken place.

Complex and lengthy poems like Egill's drápa were remembered and recited in their entirety, or not at all. The poetry of the saga is, therefore, something like its spine; it's what connects events otherwise lost in time to a linearity of possible truths. Not only did it save Egill's life, but it is also the main reason for why he's remembered.

- See also: Icelandic Literature for Beginners

Egill is also remembered as a warlock of sorts, credited as a master of the ancient runes and their magical potency. One tale tells of how, during a feast, he carved a rune that shattered a poisoned cup intended to take his life.

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Photo by Regína Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir

Not only a fearsome and seemingly indestructible warrior, but a celebrated scholar, poet and master of magic, Egill Skallagrímsson was without a doubt a force to be reckoned with, and no list of notorious Icelanders would be complete without him.

Hallgerdur Langbrok

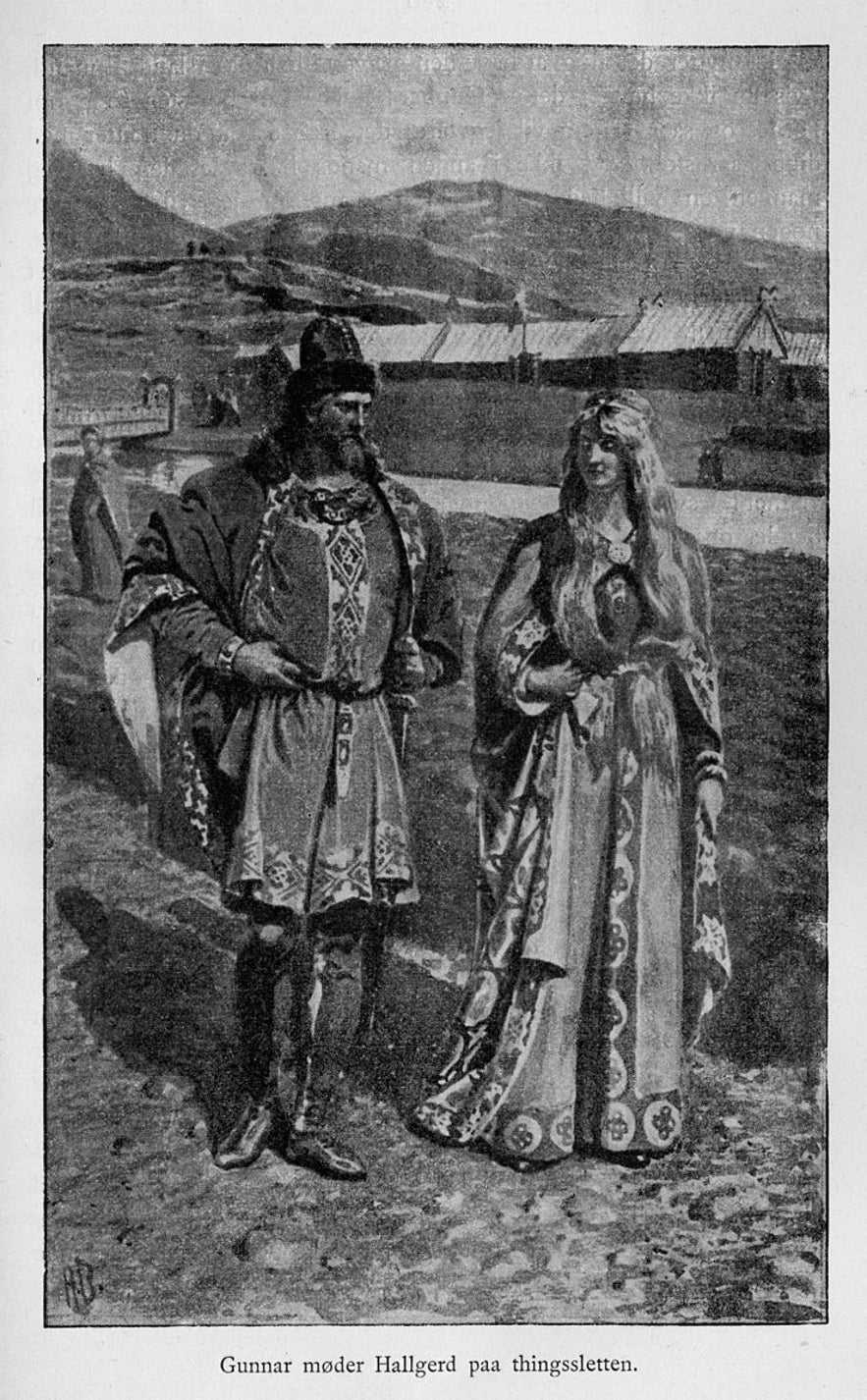

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Andreas Bloch. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Andreas Bloch. No edits made.

The first woman on our list is Hallgerður Höskuldsdóttir, also known as Hallgerður Langbrók, a prominent character in the much celebrated thirteenth-century Njáls Saga. Hallgerður was the wife of one of the Icelandic Saga's greatest warriors, Gunnar of Hlíðarendi. Renowned for her beauty and wild spirit, the feuds she inflamed lead to decades of deaths and destruction.

- See also: What are Icelandic women like?

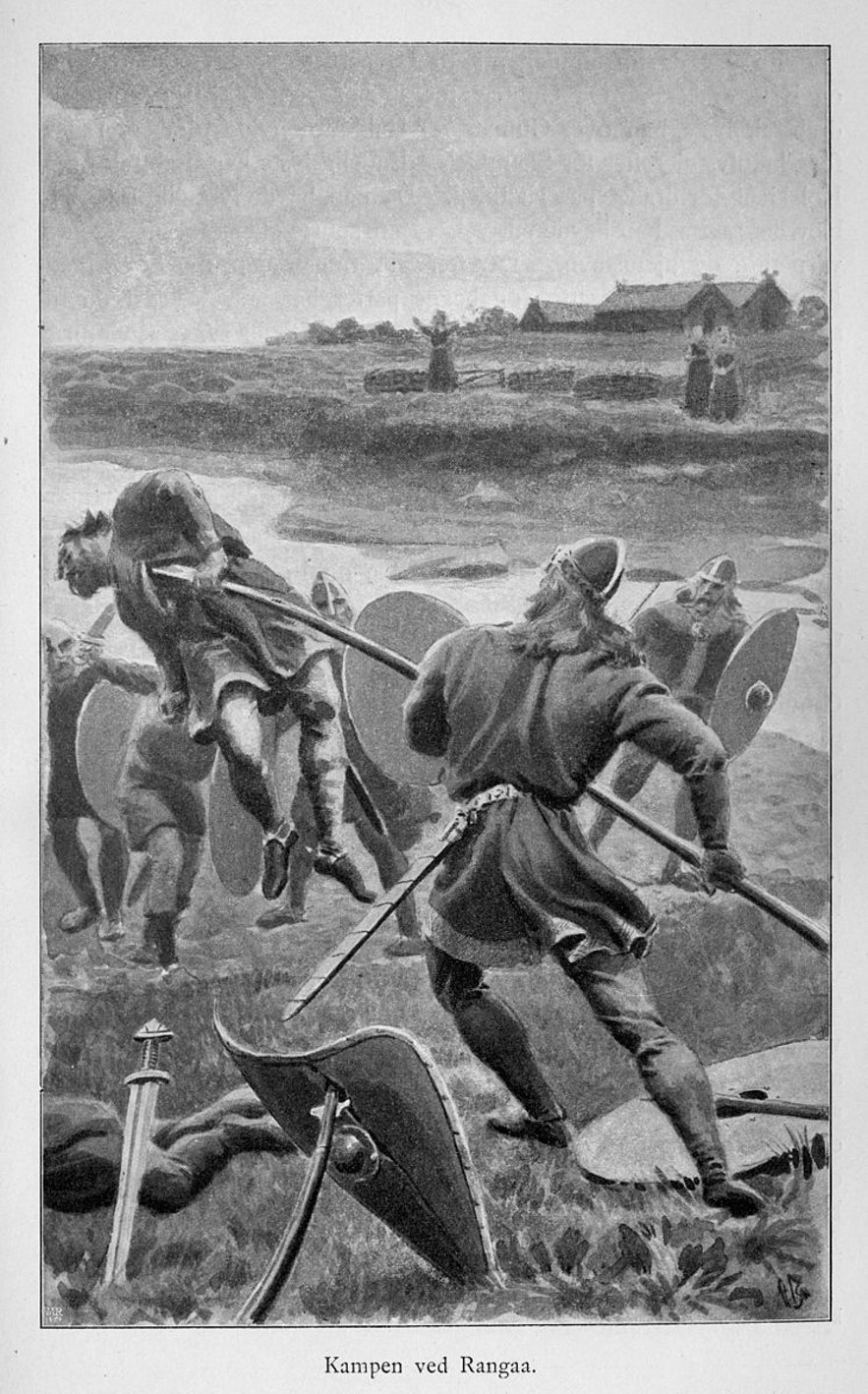

Estimated to have taken place between 960 and 1020, the events of Njáls Saga tell of blood feuds in the Icelandic Commonwealth, which existed from the establishment of the Icelandic parliament, the Alþingi, in 930 to the year 1262, when the nation pledged fealty to the king of Norway.

During this period, any insult to someone's honour had to be avenged. These continuous cycles of death are believed to be what eventually led to the destruction of the Icelandic Commonwealth itself. Most prominent of these insults in Njáls Saga are those involving blows to a character's' masculinity.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Andreas Bloch. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Andreas Bloch. No edits made.

At the centre of this destructive cycle of fragile male egos stands Hallgerður, pulling the strings to her own desires. Although never slaying anyone by her own hand, she is responsible for dozens of deaths throughout the saga.

While still very young, Hallgerður was betrothed against her will. Her first husband struck her after an argument, which made Hallgerður seek vengeance from her stepfather, a notorious brute, who killed her husband with his axe. The same fate awaited her second husband, although they reportedly had a happier marriage.

She meets her third and final husband, Gunnar of Hlíðarendi himself, at the Alþingi, where they immediately become infatuated with one another. Gunnar is gravely warned of his beautiful new bride's wicked reputation, but they get married all the same.

- Visit Þingvellir, the site of Hallgerður and Gunnar's meeting, on these Golden Circle Tours

Hallgerður soon lives up to her notoriety as she clashes with Bergþóra, the wife of Gunnar's best friend Njáll, the titular character of the saga. She then uses her charms and wits to convince various shady individuals to kill members of Njáll and Bergþóra's household.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by GDK. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by GDK. No edits made.

It is after Hallgerður sends one of her slaves to ransack a neighbouring farm, that Gunnar loses his temper and strikes his wife. She then famously states how the slap is not to be forgotten. And sure enough, at the crest of the tale, Gunnar needs a lock from his wife's hair for his bowstring. She refuses him the favour, which leads to his defeat.

Although the individuals of Njáls Saga are historical, the story is written down long after its events unfolded. Perhaps its author was merely using historical subjects to create an epic in prose.

A BBC Documentary of British scholars studying the Icelandic Sagas

Many scholars argue that the Sagas are not simply pass-time stories, but allegories, created for the purpose of preserving Iceland’s pagan world-view after the country’s Christian conversion in 1000 AD. According to these theories, the characters of the Sagas each represent particular mythological or cosmological concepts.

Scholars have also interpreted the epic of Njáls Saga as a critique of a misogynistic society, which showcases how ideals of masculinity are always and eventually self-destructive.

- See also: Gender Equality in Iceland

Hallgerður's position as a sort-of black widow of the Saga is thus of grave importance to the possible role of women in this ancient, masculine society, ruled by death and vengeance. She was certainly an influential, powerful and highly dangerous entity of the epic, which assures her a definite spot on our list.

Jon Magnusson

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by an unknown artist. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by an unknown artist. No edits made.

Icelandic history includes a long tradition of sorcery, witchcraft and magical practices. The next addition on our list, however, is not a great warlock or a wicked witch, but a priest by the name of Jón Magnússon.

Born in 1610 to a family of ministers, Jón Magnússon was a well-educated and respected member of his community. When residing and working in what is now the town of Ísafjörður in the Westfjords of Iceland, Jón fell gravely ill on body and soul.

During the peak of the European witch hunts of the 17th century, its influences reached the shores of Iceland, still a relatively recent Christian nation; resulting in what we now call Brennuöld – the burning of local witches during the period of 1654-1690.

Contrary to the witch burnings of Europe though, most of the victims in Iceland were men. Out of 170 people prosecuted for witchcraft during this period, only one-tenth were women, and of the 21 people executed for their practices, only one of them was female.

- See also: Witchcraft and Sorcery in Iceland

Two of these unfortunate souls were a father and son, both named Jón Jónsson. They resided in the farmstead Kirkjuból (also belonging to the modern day Ísafjörður) and Jón Magnússon was convinced that his illness, as well as general disturbances in the area, was due to their sorcery.

Segment from a BBC Documentary on Magical Practices in Iceland

In what has since become known as Kirkjubólsmálið, Iceland's most famous witch trial, the father and son plead guilty to the use of sorcery against the minister, who subsequently sealed their fate in 1656—death by burning at the stake.

Much to our prosecutor's dismay, this double execution did not put a stop to his illness. So what is a priest to do? Apparently, move on to the next possible culprit—Þuríður Jónsdóttir, the daughter and sister of the recently deceased Jónssons.

Her case was presented at the summit of Alþingi in Þingvellir, where it was eventually dismissed, and Þuríður was allowed to live another day. She, in turn, counter-sued Jón Magnússon for having wrongfully persecuted her, for which she received full vindication.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Johann Jakob Wick. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Johann Jakob Wick. No edits made.

In his own mind a true victim of the tale, Jón composed Píslarsaga séra Jóns Magnússonar, or Story of the Sufferings of Jón Magnússon, a written account in which he shares his many struggles and defends his case against Þuríður's.

Jón's writings were in 1999 adapted into a film by renowned Icelandic filmmaker Hrafn Gunnlaugsson, called Myrkrahöfðinginn or Prince of Darkness. An interesting adaptation of the historical tale, where its tragedies are less the fault of Jón's delusional insanities, but rather the times being ruled by Christian fear-mongering against witchcraft.

- See also: The Story of Icelandic Cinema

Whatever the case, Jón Magnússon was, without a doubt, a terribly troubled man. Whether it was due to his illness, his faith, or his hatred, people paid with their very lives.

Fjalla-Eyvindur and Halla

Sharing the next spot on our list is an infamous pair of outlaws. Fjalla-Eyvindur, or ‘Eyvindur of the Mountains’, and his wife, Halla, reportedly lived together in the wilderness of the Icelandic highlands for twenty years.

Look at a map of Iceland today, and you'll notice several locations exhibiting Eyvindur's name (Eyvindarver, Eyvindarsandur, etc) where he and Halla are thought to have made camp.

In Icelandic culture, the outlaw is a prominent figure of interest. An outlaw is someone who, after a grave disagreement with the law, retreats into the wilderness to reside outside of society. These individuals were said to be sheep-stealing bandits and could be legally murdered on sight if spotted.

Fjalla-Eyvindur and Halla historically existed as recently as the 18th century. As so often with the stuff of legends, various fictional accounts surround their story, but documented descriptions do exist of them in Alþingi reports from 1765.

One is reminded of the phrase 'opposites attract' upon reading these descriptions. Eyvindur is said to have been fair-haired, good-tempered, clean, diligent, athletic and soft-spoken, while Halla is described as being foul, unseemly, husky and generally abhorrent.

These descriptions continue in folklore, where Halla is said to have waited outside while the rest of the community went to church on Sundays. A woman too devilish to enter a church? Or a case of character presentation gone haywire? Whatever the case, Eyvindur is definitely the more famous and celebrated of the pair, while Halla is decidedly more vicious.

It is not clear as to exactly why the pair was exiled. Before their escape, Halla wanted to burn the farm in which they resided, but Eyvindur convinced her not to, thus saving the children sleeping inside. This horrid theme of infanticide (the crime of a mother killing her child) follows Halla throughout the entire narrative.

Eyvindur and Halla supposedly had many children together, but Halla terminated them all upon birth. Although Eyvindur reportedly wanted nothing to do with these killings, he didn't stop his companion either. But there was one child whose death he mourned the most, a girl who had been allowed to live past her first year.

Until that is, the couple was detected by nearby farmers and yet again hunted for their thievery. They had to make a hasty escape, so Halla threw the girl child off a cliff. In later retellings of this story, she is said to have rocked the child to its last sleep with a now famous lullaby, Sofðu unga ástin mín—a lullaby Icelandic parents still sing to their children today.

The infamous and hauntingly beautiful lullaby, sung on a collective of folk songs by Icelandic singer Ragnheiður Gröndal

Eyvindur's crimes are noticeably less horrid and mostly include theft of sheep and horses. Even so, his vices are endearingly excused as being well-meant or necessary. Early on, he was said to have stolen a wheel of cheese from a wandering old woman. She cursed him for it, making it so that he'd be committed to a life of theft.

The story goes that after twenty years in the mountains, the couple returned from exile to Halla's old farm at Hrafnsfjarðareyri, where they eventually died.

Another version of the pair's demise is that Halla was apprehended by the authorities, but deemed too weak to be imprisoned. She spent her last summer at a farmhouse in Mosfellssveit, looking at the mountains. One autumn day she remarks on how they are beautiful once more, and the following day she disappears.

Several years later, the skeleton of a woman was found in the nearby mountains. It was assumed to belong to Halla, as she had gone to the mountains to be with her lover once more.

If Halla is the true villain of the tale, Eyvindur is perhaps more of its anti-hero. All the same, the notoriety of the pair is undeniable, ensuring them a definite spot on our list.

Jorundur the Dog-Days King

Jørgen Jørgensen, known by Icelanders as Jörundur hundadagakonungur or Jörundur the Dog-Days King, was a Denmark-born explorer and adventurer. Why include him on our list of infamous Icelanders? Read on to find out, for his is a captivating tale of roguery and exploits.

Jørgensen, born in 1780, was the son of the royal watchmaker of the city of Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark. After having mastered studies of seamanship at the age of twenty, he joined the British fleet and began his many escapades.

Falling in love with England, an oddity for a Danish person of the time, Jørgensen didn't return to his homeland until late in his twenties. But in 1807, British war vessels attacked Copenhagen and seized the city, resulting in Denmark declaring war against the United Kingdom.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Francis Sartorius Jr.. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Francis Sartorius Jr.. No edits made.

As a result of all able-bodied Danish men being drafted into the army, Jørgensen was named Captain of the Danish war vessel Admiral Juul. He was ordered to sail to France to recruit soldiers but instead opted to frolic around in English waters. He was subsequently seized by the British, who treated him as a privateer, and decreed guilty of treason in Denmark.

Jørgensen then convinced his merchant friends in England to venture to Iceland, a voyage he said should be highly profitable since the Icelanders were plagued by the Danish monopoly on local trade. Because of the war against England, no Danish ships had arrived in Iceland bearing goods, leaving the country in a state of famine.

Arriving at the shore of Hafnarfjörður in January 1809, Jørgensen and the rest of his crew were regrettably forbidden from selling goods to the Icelandic people, by the acting Danish governor Frederick Trampe. This did not stop our rebel explorer, and he returned the following June with quite the counterstrike.

- See also: Iceland in June

Upon their return, Jørgensen and his crew apprehended Trampe and locked him away on their ship. The following day, Jørgensen signed and released a now infamous proclamation, where he declared Iceland free and independent from Danish reign.

Additionally, he named himself its protector and highest power, until the Icelandic people would be able to govern themselves. Until then, any opposing party was to be executed. A leader to set us free?

So to recap: a Danish outlaw and a prisoner of war of England breaking parole, Jørgen Jørgensen revolted against his own and essentially declared himself King of Iceland. He had a fort built on the location of modern-day Arnarhóll in the city centre, drew up a flag, and thus the Dog Days began.

Why were they called the Dog Days? It has to do with astronomy; the Ancient Greek associated high summer with Sirius or the 'dog star' – the brightest star in the Earth's night sky. Anyone who has resided in Iceland for the high summer might be familiar with the days never ending, and the parties never stopping.

- See also: Nightlife in Reykjavík

No party can last forever though, and two months later Jørgensen's rowdy reign came to an end, as the British warship Talbot arrived, and Trampe managed to escape.

Jørgensen went on to be arrested for having left London, but not before he saved the crew of the ship that was transporting him from a fire. In prison, he got a knack for playing cards and writing. Essentially, his adventures had just begun, which mostly included drinking, gambling, and bending or breaking every rule in the book.

A traitor, liberator, crusader, or ruthless invader? Whatever his title, the Dog Days King shook things up at a momentous time in Icelandic history and indefinitely marked his spot in it – and on our list.

Axlar-Bjorn

We must admit we saved the worst for last, for topping our list of Iceland’s most wanted is none other than Björn Pétursson, better known as Axlar-Björn, Iceland’s only known serial killer in history. Born in the late 16th century, this ruthless murderer got his nickname from the farm in which he resided, Öxl in Breiðuvík in the Snæfellsnes peninsula.

Many mysteries surround the bloody story of Axlar-Björn, and he has long been a subject of fascination to writers, poets and historians. The only verified documentations of his life are those found in the 1596 and 1597 verdicts of Alþingi, Iceland’s legislative body. However, folklore and numerous stories tell of his many crimes, and perhaps these accounts can help us unveil the man behind the myth - if a man is what we can call him.

- See also: Folklore in Iceland

Born to a low-income family, Björn was taken into foster care by his father’s master at the age of four. During his first years, he did not differ much from his siblings or stepbrother, Guðmundur Ormsson, with whom he became close friends.

It wasn’t until his teenage years that his disorders reportedly surfaced, when he grew cold and antisocial. One legend tells of how Björn fell asleep during Sunday mass and dreamt of a man offering him copious amounts of red meat. Björn gleefully devoured the pieces one by one, until finally feeling sick after the eighteenth.

This particular folklore is undoubtedly based on the number of Björn’s victims, although there is no way to know exactly how many fell to his prey. On trial, he admitted to them being nine, but several accounts believe they were as many as eighteen.

After the passing of his father, Guðmundur Ormsson built his stepbrother the large and lavish farmstead Öxl, where Björn would reside with his wife, Þórdís Ólafsdóttir. This was to be the location of the horrors that Björn freely committed for all those years, where unsuspecting travellers sought shelter at his land.

Instead, they wound up in pieces in a watery grave, a deep pond on the premises by the name of Ígultjörn. The victims were stripped of their goods, clothes and horses, supporting the reportedly lush lifestyles of Björn and his wife.

How could a whole farm not know of over a dozen murders taking place? With new horses regularly appearing in the stables, chances are that they did, but kept quiet because of the influence of Björn’s adopted family.

In the writings of Sveinn Níelsson, Guðmundur is said to have visited Björn at this farm to confront him about his crimes. Björn then came after his stepbrother with an axe, managing to wound his horse as he barely escaped. Afterwards, Þórdís asked Guðmundur to keep the incident to himself. He agreed but added that sooner or later, the wickedness of Axlar-Björn would be discovered.

There are different tales as to how this homicidal maniac was finally apprehended. One tells of a mother and her three children who spent the night at Öxl. Björn lured the children away one by one and brutally killed them, but their mother escaped and alerted the authorities.

Another version describes how two children, a brother and a sister, were staying at the farm overnight. After supper, Björn escorted the girl from the room, when her brother was suddenly startled by her screams. Terrified, he ran outside to hide in the stables, with Björn fast on his heels. The boy spent the night on the run, before finally escaping to the nearby farm Hraunlendi.

There, the farmer took the boy to see the sheriff of Brekkubær, who subsequently returned with a few strong men to face Björn at Öxl and arrest him, thus finally ending his reign of terror. The evildoer was tried at Alþingi in 1596, and his sentence was death by beheading.

If that wasn’t enough, his limbs were first shattered with a sledgehammer, and his private parts cut off and thrown to his wife. As for Þórdís, her husband named her a culprit to the murders, and as a consequence, she was also sentenced to death. However, reports claim she was with child at the time, so her execution was postponed.

Evil seemed to run in the family - Sveinn skotti, the son of Björn and Þórdís, lived a vagabond's life of crime and mischief until arrested and hanged for attempted rape in 1648. His son, Gísli hrókur, later met that very same fate.

One of Iceland’s most renowned poets and lyricists, Megas, masterfully adapted the tale in his 1994 novel Björn og Sveinn, where the father and son duo travel the modern underworld of Reykjavík together.

Although the facts are littered with myths, Axlar-Björn's is a story stained with blood and one the Icelandic people are not likely to ever forget - guaranteeing him the top spot on our list.

Whatever their crimes, these colourful individuals are all remembered by the Icelandic nation as being larger than life. From the beloved Egill Skallagrímsson to the loathed Axlar-Björn, these oddities and outcasts all contributed to the shaping of their nation’s history - for better or worse.

Who is your favourite villain in Icelandic history? Did we leave anyone out? Let us know in the comments below!